by Joe Parkin Danniels / The Guardian

The mining operations have left their mark on the landscape around Lake Izabal. Photograph: Joe Parkin Daniels/The Guardian

A decision to restart operations at one of Central America’s largest nickel mines is being questioned by campaigners, after an investigation appeared to show the company co-opted indigenous leaders and smeared potential opponents.

In 2019, the Fenix project in eastern Guatemala was the subject of an investigation carried out by the Guardian and other media, organised by French consortium Forbidden Stories.

In that investigation, residents alleged that the mine – which is owned by Solway, a company based in Switzerland – was to blame for failing crops, polluting the lake and pressing local authorities to quash dissent.

As a result of a new investigation by the same consortium, the Guardian visited local communities in El Estor, the municipality surrounding the mine, in January this year and heard from residents and community leaders that claim little has changed.

“They said that there would be development [building schools and hospitals], that there would be a change in El Estor, when really there is none,” said Cristobal Pop, 45, the president of the artisan fishers’ union.

Officials in Guatemala overturned a suspension of the mine’s extractive activities in January. The suspension had been imposed after the Central American country’s constitutional court ruled, in July 2019, that the mine had been operating since 2005 without having consulted local indigenous communities, as required under international labour law.

The Fenix nickel mine in eastern Guatemala. Photograph: Joe Parkin Daniels/The Guardian

Smear allegations

Guatemala’s ministry for mines and energy said the consultation had “concluded in a satisfactory way”. However, some indigenous communities allege they were not fairly involved.

“It wasn’t a consultation, consent was never given by communities, who didn’t have information or freedom,” said Pop, whose fishers’ union brought the case before the constitutional court after a mysterious red stain spread across Lake Izabal, the country’s largest expanse of fresh water, in 2017.

Several consultation meetings took place from September to December last year between representatives from the mine, the government and indigenous communities.

However, campaigners allege that many of the indigenous leaders included in the consultations were supporters of the mine, and that many members of the community were not consulted.

According to information obtained by Forbidden Stories, donations to a foundation linked to the mine appear to have been used for “economic support” to members of one indigenous organisation included in the consultation.

In information obtained during the investigation, mining employees also appeared to float the pros and cons of different rumours that could be spread about members of the community, including that some leaders had HIV.

The mining company said that foundations in Guatemala are “regulated by the law on non-governmental organisations which defines the rights of foundations not to disclose information on sources of donations and expenditures”. It said the community consultation was conducted by the ministry of energy and mines, as the constitutional court named it in its ruling as the body responsible for carrying out the consultation.

Separately, the new investigation uncovered evidence that representatives of subsidiaries of Solway gave Christmas presents to journalists, priests, labour leaders, judges and mayors in the communities of El Estor and the surrounding area in 2016.

The company said that giving Christmas gifts was not out of the ordinary. “It is a common practice in Guatemala to send Christmas baskets to friends with whom one has interacted during the year. Christmas baskets are only given to individuals when it is not prohibited by law,” said a spokesperson.

Local residents’ fears

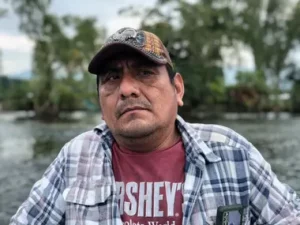

Cristobal Pop, whose fishers’ union brought the case against the nickel mine. Photograph: Joe Parkin Daniels/The Guardian

On visiting several communities around the mine, the Guardian found that many residents from Maya communities are afraid that they may be forced from their lands.

“We don’t want to be relocated,” said Dominga Chub Chub, 28, a resident of the Las Nubes community, which partially sits on land claimed by the mine. “If the company comes and forces us out, where will we take our children?”

Other residents feared life in the community would worsen.

“The community on this tract of land is at risk of extinction,” said Luis Caal Che, 58, who once led Las Nubes as its mayor and would often negotiate with representatives from the mine. “This community will remain in poverty, the mine will have what is ours and our crops will no longer bear fruit.”

The company said it invests in local communities and does not plan to relocate the residents.

According to the investigation, there was a significant environmental incident in November 2020, when tonnes of bunker fuel overflowed or spilled, affecting the outflow channels and Lake Izabal. The company said the spill was contained and controlled and that “at no time was the outflow channel or Lake Izabal affected”.

Luis Caal Che: ‘The mine will have what is ours and our crops will no longer bear fruit.’ Photograph: Joe Parkin Daniels/The Guardian

Fisher Oscar Cuc Tiul, said that fish populations in the lake continue to dwindle. “There is so much contamination,” he claimed, adding that he now catches deformed tilapia and bream, sometimes referred to by local people as “devil fish”.

Protests against mine

Protests against the mine broke out in October last year in the run-up to the consultation, with demonstrators angry at what they saw as a rigged process. Roadblocks were put up, cutting off access to the mine and processing plant.

The government responded by declaring a “state of siege”, limiting freedoms for 30 days and imposing nightly curfews, while soldiers arrested supposed instigators.

“That’s when we could see that the government is in favour of the company, even co-opted by it,” said Olga Che, the treasurer of the fishers’ union and a member of the Council of Ancestral Q’eqchi’ Authorities, whose home was raided after attending protests.

The landscape around the nickel mine. Local farmers said crops were failing and blamed the mining operations. Photograph: Joe Parkin Daniels/The Guardian

Activists accuse the municipal government of siding with the company in disputes, which officials deny.

In a statement, Solway said it “refutes the allegations that are without factual basis. Solway is operating in line with applicable laws. Regarding a responsible corporate governance according to international standards, we have taken actions which are also being followed up in dialogue with both the Swiss state secretariat of foreign and economic affairs and the Swiss embassy in Guatemala.”

Campaigners say they will continue lobbying the government and the mine for a consultation that includes wider representation. “We are going to carry on,” said Pop. “We will not recognise that consultation for as long as we are alive.”