Cross Posted from El Enemigo Comun

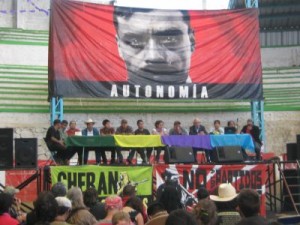

The Cherán K’eri uprising on April 15, 2011 and the process of self-government now underway in that community is, for many, a source of inspiration, a strong show of resistance to be defended, and an experience to learn from. That’s why around 500 people from 15 cities in Mexico and 11 countries in the world set up camp just outside this Purépecha town in Michoacán on May 24-27, 2012, as part of the National Encounter of Autonomous Anti-Capitalist Resistance. The idea was to lend support to the Cherán community and share experiences of autonomy, options of self-organization, and ways of living in harmony with nature.

During three marches through the streets of the town, people shouted: We’re with you, Cherán! You can count on us, Cherán!

In the inauguration ceremony in the main plaza, the Town Council of Cherán welcomed everyone, and spiritual leader José Merced pointed out that this is not Cherán’s first insurrection. During the Mexican Revolution, Cherán rose up in arms. He said, “In Cherán’s new self-government the K’eri are the councils directly chosen by the people, shutting out the political parties and politicians seeking power. In Cherán K’eri they’re a thing of the past!… We welcome you with all our heart regardless of age. Youth is something we carry in our hearts. We´re forever young in our hearts and souls — young warriors forever.”

In the ceremony, Eduarda of Radio Ñomndaa read a document about autonomy that spoke of Cherán as an example of struggle, dignity and resistance. A statement by the Autonomous Anti-Capitalist Resistance Network was also read which defined four avenues of resistance: blocking the flow of capital, ending the war on the people of Mexico, defending Mother Nature, and building autonomy. Messages of support were read from Occupy Oakland and Barcelona’s indignant movement. The announcer asked for a moment of silence for ten community people killed in defense of the forest and the community, and a traditional ceremony was then held in which four young girls presented the beautiful flag of the Purépecha nation with the symbol of the great fire in the center and the inscription Juchari Uinapikua, Our Force, written below.”

The same afternoon in the main plaza, the first forum was held with speakers from the Brigada Callejera, FPFVI-UNOPI and Radio Ñomndaa, groups that have spent years on paths of resistance, autonomy and self-organization. The first group began organizing sex workers in the area of one of the oldest urban markets in Mexico City and now has chapters in 28 states, the second has concentrated on housing problems and the creation of cultural and educational spaces in urban neighborhoods, and the third helped establish the autonomous municipality of Suljaa on the Costa Chica of Guerrero and set up a radio station in the amuzgo language, Radio Ñomndaa, Word of the Water, under heavy repression from local power bosses and governments of all political parties.

In the days that followed, activities included fire ceremonies, workshops, dialogue tables, forums, video screenings and cultural programs featuring traditional music and dances of Cherán along with a little rap, reggae dub and ska.

On May 26, the last night of the Encounter, a forum was held in which Ignacio del Valle of San Salvador Atenco was one of the speakers. He recalled the words of a federal police chief: “Get out of our way because we’re going to sweep you off the streets.” “But we decided not to be swept off the streets,” said Nacho. “We will never forget the way they attacked us, but we have to move on ahead, refusing to give up or give in.” Other participants from Cherán included the young people of Radio Fogata and the Community Patrol, as well as a member of the Cherán Town Council, who recalled that the community had been divided by the indolence and selfishness of six political parties that allowed the destruction of the forest, the water, and the life of the community until a group of brave women, along with the youth of the town, put an end to the abuses. He stressed that there are no leaders in Cherán, where “keeping a tree alive is support for life itself.”

The applause was overwhelming when Angelina took her place on the platform. She reminded people that before April 15, 2011, townspeople weren’t free to walk in the streets at night. “We had to take action for our children’s sake,” she said. After running out the clear-cutters, the women spent many cold nights around campfires in defense of the community. “We used to be afraid,” she said, “but now I’m happy because we’re doing pretty well and we’re freer than we were before.” The next speaker was Alicia, a member of the Dialogue Commission, who spoke about how a handful of women had to break with despair and humiliation in order to take the lead in the defense of the forest and the community.

In the forum, the anthropologist Gilberto López y Rivas reminded everyone of the military and police penetration of the United States in Mexico and of that country’s imperial strategy. He said that in Cherán we have seen how autonomy can be a way to struggle against organized crime, but autonomy is not always a positive thing. We have to give it content, he said, and the key to that is self-transformation.

On May 27, the Encounter ended with a spirited march (the third) from the camp to the center of town. A contingent of townspeople joined in, dancing joyfully in lines that wound through the streets to the music of the Cherán brass band.

At the closing ceremony of the Encounter, participants voiced our support for the freedom of political prisoners Alberto Patishtán Gómez and Francisco Sántiz López, demanded justice for San Juan Copala, and repudiated the evacuation of the Altépetl occupation in Mexico City. We reiterated our support for Cherán and approved a proposal of the Autonomous Anti-Capitalist Resistance Network to hold a series of national solidarity activities with the people of Cherán.

The voices of some people of Cherán interviewed by this reporter are transcribed below; in two cases other members of the free and independent media participated in the interviews:

Guille, a Cherán woman, speaks:

“It was really early in the morning. A lot of people hadn’t gotten up yet. I was one of the first people to respond to the call for action. I was really worried because of all the fireworks set off in the area where the conflict began. Here, we use fireworks to communicate with each other when something important happens in the community. When people hear them, we unconsciously count how many have sounded. If there are more than three, we go out into the street to see what’s happening. That day it seemed like hundreds were set off. Then the church bells began to ring and that’s always a sign that something really big is happening. It’s like saying: Watch out, Cherán. We’re in deep trouble.

“I work in a nursery and before that day I just did my job. I hardly ever went to meetings. When they were clear-cutting, a lot of people were threatened and there were even kidnappings and extortions. After 7 o’clock in the evening, we couldn’t walk around in the streets. We had to stay inside because that’s when they came in to cut down trees, and if they saw people on the streets, they threatened us. They began to come down the mountain with the wood around 3, 4, or 5 o’clock in the morning.

“There were meetings to talk about what to do, and they were held more frequently after three people from the Communal Property Commission were disappeared on February 10, 2011. In the meetings, there was a lot of division over peoples’ proposals and none of us dared to say ‘enough is enough’ because we were afraid. But April 15 wasn’t a day like any other.

“When I went to see what was going on, I found out that a neighbor had been wounded and that there was a need to support the women who were taking action. I started walking through the streets telling everybody to block the roads because the trucks were no longer allowed in the community. I wanted more people to come out to support these women. So from the very first day, I was with them.

“I’ll just explain what they were doing there. Every Friday it’s customary for all the women to sweep the streets of the town really early in the morning, around 6 o’clock. So that day, the group of women sweeping in the area of El Calvario church were the ones who started the whole thing. There must have been about twenty of them. It was always a sad sight to see those trucks coming down the mountain loaded with wood, and that day several of them came down at the same time right around 6 o’clock in the morning. Those women just started throwing stones and fireworks at them. Nobody said, ‘Today’s the day’, or ‘We’ll begin at such and such an hour’. Things just kicked off. It was spontaneous”.

“When they heard the fireworks and the church bells, a group of young people joined in almost immediately, and then a lot more neighbors did, too. Seven trucks were burned and five men were detained. The rest got away with the help of our local police. From that time on, we stopped recognizing the authority of the police. Most of them weren’t even from here. And in fact, they were working with the organized crime group. The people detained were held for seven days.

“From then on, we began to have meetings every day at 6 o’clock in the evening, at first in the El Calvario neighborhood and then at established points in each of the four barrios. The general meetings were held in the center of town. It was really heavy because we’d never been through anything like that before. Some people took quite a long time to get over their fright and come out of their houses.

“It’s almost impossible to say what I felt at the time. I felt a lot of impotence when I thought we weren’t going to be able to stop them because they were armed and we weren’t, but at the same time, that very impotence made me angry enough to keep on. We couldn’t stand by and do nothing just because they had arms. We didn’t know what was going to happen, but fortunately, I think we’ve put a dent in the number of trees they were chopping down, and above all, I think we’re more free than we were before.

“The barricades were put up that same day. Campfires were also lit on the street corners every night. How? We don’t know. It was almost instinctual. ‘I’m here on this street corner and I’m going to protect my area.’ Nobody told us: ‘You, make fires. You, put up barricades.’ There were no leaders, and the community patrol wasn’t organized until later on. We were unarmed. All we had were the groups of guards organized around the fires. Women, men, young people and children joined in.

“I think we began to practice autonomy the moment we decided to stand up to those people. Why don’t we want municipal presidents and all that? Because they’re part of the game. If we accept them, it would be the same thing as allowing our forests to be destroyed even more than they already have been. The politicians are hand in hand with organized crime.

“From that day to this, we’re different. And struggling, fighting to be different has cost lives. But in honor of those people who have given their lives for this struggle, we’re going to keep on doing all we can to protect Mother Nature, which is our life. I feel calm and peaceful. I identify with what’s going on because I lived it from the very first moment. I don’t have children, but I have nephews, and I want them to live free.

“There’s still a lot of uncertainty because we haven’t achieved all that we want to. We haven’t been able to get them to leave our territory alone. Even though they’re not clear-cutting here, they’re taking out wood from other areas. Not as much as before, but we still can’t breathe a sigh of relief. We want them to leave our forests in good shape.

“There are brigades of men who go up the forest every day to watch over them, reforest, rehabilitate, and clean them. It’s really dangerous. Unfortunately, we’ve lost more lives in our attempts to rescue the forest.

“Some people are sorry they got involved, especially those who had an interest in the power struggles of the political parties. But those who were looking for a position of power in the town government were shut out, and in a way, defeated. Once again, they’re trying to disintegrate us, but we hope they won’t be successful. We’re still strong and we’re united. We’re in the majority. In our movement there are people who never had anything to do with the political parties. I think we’re on the right track. We haven’t gained everything we want to, but we’re safer than before. And we’re free.

“The only thing I’d like is for people who read your article to analyze the movement and see that it has nothing to do with the interests of a small group of people. The benefits are going to be for everybody. We all love the planet. The trees give us life. They give us water. And we have to respect their lives, too.”

Voices of the Community Patrol

Interview done in conjunction with María X and Elena

“When they were cutting down trees up on the mountain, they passed through the town and we had to get out of their way because they were armed. That’s why we were afraid. We had asked the government to stop the clear-cutting, but as usual, those authorities don’t do a thing for the people. It’s just one promise after another. Even now, nothing at all has been resolved by the government –– only by the people.

“When this movement got going, the people who started it were the women. It was around 4 o’clock in the morning when they began to stop the trucks and set off fireworks. And people started gathering near the chapel in the third barrio called El Calvario. That’s where it all began. A lot of people turned out. We blocked the street with stones. Nobody could come into the town. We put up the barricades and lit the campfires, and people brought us food at night. But at first, the Community Patrol didn’t exist. We rose up unarmed, and it wasn’t until later on that we armed ourselves.

“Some of the people proposed the formation of the Patrol and invited young people to sign up. I was invited to join, and I’ve been part of it since two months after the conflict began. Why? Because I wanted to be on the side of the people. I wanted to defend them. I wanted to make sure those criminals couldn’t come back. That’s why we got organized.

“We’re volunteers. Nobody says: ‘You, come over here’. From the first, we were the ones who started arming ourselves. Personally, I really like this movement. It’s against those guys who were cutting down our forests. We have four barrios here, and we each watch over our own barrio. At first it was pretty tiring to be here day and night, but now we’ve gotten a little better organized. We come in at 10 o’clock in the morning and leave at 10 o’clock at night. Then another shift comes in and we can rest for a while.

“We don’t have any bosses. All of us are together here. Anybody in the Patrol can answer any question you want to ask us. We all know what’s gone on here and what’s going on right now. We’re here of our own free will. Now we have coordinators, but the decisions are made by all of us.

“We’ve achieved some of our goals. Now they’re not clear-cutting around here, although they are still taking out wood from that hill over there through a ranch called Cerezos. But since we’ve been standing guard, the situation has calmed down. They haven’t disappeared any more people here in Cherán. People can walk around freely at night because they know we’re here at the entrances to the town. We’ve set up our own government. We don’t want to have anything to do with the political parties because all they do is create divisions. Instead, everybody is working together now.

“There are people who are against the movement. Most of them are in the wood business, but they’re only about an eighth of the community. Most people agree with us. The situation is still tense. In April two community people were killed and today they found the body of another person. We still don’t have all the details of what happened. All the people we kicked out probably want to come back. But they’re not going to be able to. We want to thank all the people who’ve supported us.”

From Radio Fogata, Ángel y Mauri talk about their project

Interview conducted along with Alejandra of La Voz de Villa Radio

Mauri: The name of the radio has to do with the way the community got organized around the campfires when the movement first started on April 15, 2011. We chose the name Radio Fogata because of these campfires and also because, for the Purépechas, fire is a major symbol and a way to get organized. The radio began as a workshop for young people …. Most were between 15 and 20 years old…. We talk about problems of migration and the environment and about women’s issues. Other community groups also participate in the programs. We’ve invited the children several times, for example. They’re really interested in taking care of our natural resources.…

Ángel: One of the reasons we decided to start a radio is to inform the townspeople and communicate with them. In the past, there wasn’t a way to communicate with people when there were meetings or events or when something important happened. There is another radio in Cherán, but it belongs to the government and it’s never broadcast information about what’s really happening.…

Mauri: Yes, as a matter of fact, that radio was once taken over. The whole community came out against it because it never said anything about what was going on here. Then, after the workshop, we started this radio with people who’ve never worked at a radio station but who want to support the community somehow…

Ángel: Beforehand, I was a high school student. At the time, there were no classes and I didn’t have anything to do, so I decided to pitch in. I was just staying at home doing nothing, and we’re never going to get anywhere that way, are we? So one day I decided to get out of the house, and I heard about the radio workshop. I said to myself: Come on, let’s go. Let’s see what this is all about.

Mauri: I didn’t have any experience in communication. I also heard about the workshop and it sounded interesting. I never believed I’d be part of a radio project one day and that I’d be broadcasting programs about the environment, which I did have some experience in. I used to study in the School of Biology in Morelia and I’m really interested in nature. So when I did join the radio collective and saw a lot of the environmental problems we have here in the community, I decided to do a program with a comrade and get out information to all the youth, all the people, all the children, telling them that we have to change our way of relating to nature and start taking care of our resources so we can be in peace with ourselves and our natural environment.

Ángel: The main satisfaction you get from working in a radio collective like this is that you change as a person. You stop thinking that everyone is happy and that everyone is a good person. You totally change your way of thinking about the political parties, about the way people get organized, about what’s happening in the world. You get more interested in what’s going on around us.

Mauri: You learn a lot from everybody that comes to visit, from all the collectives that come here from other parts of the country and other parts of the world…We’ve realized that we’re not the only ones with community problems…You have a lot of new experiences and you learn a lot from them, and you feel good because you know people are listening to you on the radio and you can change the way a lot of people think.

Ángel: A message to other young people? Open your eyes. Don’t be fooled.

Mauri: Yeah. Don’t believe what they put out on the major news media. Get motivated. Pick up a microphone. Pick up a camera. Pick up all possible tools of communication to get out the whole truth and not just part of it…. We young people are the ones who can change society. We can demand a lot of things because we’re the ones who are going to be here later on and we’re going to suffer the consequences of all the bad things that are being done right now… There’ve been a lot of changes here in the community. I feel safer now, because in the past, even the policemen themselves were corrupt. There was no security at all. There was no trust… But now a lot of people think different, and with this movement the whole community has gotten organized and protected each other. Now I feel safer and really happy because I belong to Radio Fogata and I’ve been able to express myself.

Ángel: Before April 15, there was a lot of talk about the problem of our trees being cut down and people felt really bad, but because of the fear of so many things like forced disappearances and shootouts, nobody wanted to stand up and say, ‘No. Stop. This is mine. You have no business here. You’re not part of this community.’ People really wanted to do something, but fear stopped us until that day when we saw the chance to rise up and kick those people out who were robbing our wood, our trees.

Mauri: The problem that made people decide to rise up had existed for a long time, two or three years before April 15. And because we were afraid those people were going to do something to us, nobody did anything until then. In reality, people began to get organized on April 14, then the next day they decided to meet those people with sticks, stones, bottles full of gravel and gasoline with a piece of flannel stuck in them. People were tired of seeing those trucks come down loaded with wood ––not 2 or 3, but 20 or 25. So when the community was getting better organized, people decided to meet them on their own terms. It was ugly. I’ve never forgotten and I’ll never forget the women screaming and children crying. The church bells were ringing and ringing. There was a lot of fear. You wanted to go out and stop those people who had done so much harm to our forest anyway you could, with gunfire or stones. The deep-seated anger against them was really ugly. People were able to capture several of them. And that’s how our movement began. That’s how more movement got started here in the community towards more organization, and we were finally able to set up our own government.

Ángel: That day I felt really frightened because my school is right there on the road out of the community…I saw one of those 4-wheel drive trucks piled high with people trying to get away. There were a lot of students out there. A disaster. The teachers were really concerned. I felt like running out and doing something, but then that fear come over you. You ask yourself: What do I do now?

Mauri: People got fed up. And since the government didn’t want to do anything against them, the community decided that we ourselves had to stop them. That’s how it happened. There was no strategy or anything like that. Just rage. Since the clear-cutters were armed, people were afraid of getting shot down ––up until that day when they hid behind bushes and on street corners and lay in wait for them. One community person did get shot in the eye and ended up in a wheelchair, but he was brave enough to do something for his community, so he must feel good about that.

Mauri: [The process of organization] was a long one. That day after running them out of town, even though people might have wanted to get together and get better organized, there was still a lot of fear. Cherán was a ghost town for months, maybe three months, where hardly anybody dared go out in the streets, not even the dogs…. But at night, groups of people went out to protect people, made up of maybe 30 people who lived on the same block, 10 at a time while the others rested. That’s the way people gradually got organized and the community began to recover. The barricades are still there, but the campfires are not. Things have gotten back to normal. We have our community police and good organization.

Ángel: [We began to talk about autonomy] when people realized the government wasn’t going to do anything, mainly because of one of the political parties.… But we didn’t want to go on that way. We were tired of all the lies, so much talk and no action. And that was one of the main reasons we decided to govern ourselves. Now people are chosen to serve on a council not because they are popular, but because of their character, their values, their knowledge, which may come from schooling or from life experience. There’s a lot more trust in them and I think they’re going to do a much better job than the political parties.

Mauri: The political parties don’t do anything right. It’s better to have organization like we have now here in the community and choose our own self-government without the involvement of any political party. They don’t do a thing for the community, only for themselves.

Ángel: The radio workshop was held three months after the confrontation when everything had calmed down. A concert was planned and one workshop participant said, ‘I’ll get you a transmitter and if we can’t get hold of one, we’ll make some radio speakers. We can have an event to talk about what’s happened since the very first day up until now”. Then some people from his collective helped us do our first broadcast and encouraged us to set up our own radio.

Mauri: Our friend at Radio Vecindad really supported us. She loaned us her tape recorder and suggested that we go out to the campfires to interview people so we’d have material to broadcast over the radio. And with her tape recorder, we began to ask people about the uprising that happened here and about what they had against the previous government –– the lack of security, the overprotection of the clear-cutters. As a matter of fact, in YouTube there are videos of their communities. If you type in ‘Capacuaro’, you’ll see videos that they themselves made, showing how they cut down the pine trees. And they show newscasts making fun of our community and our government. They’re not interested in how people got organized and stopped the destruction of the forests. They’re protected by the government.

Ángel: Thank you for visiting us. I hope people who hear about all this will want to do something for our environment, for our society so we won’t keep on falling into the traps of the self-serving political parties.

Mauri: We’re not making up stories. We’ve talked about things happening in our communities. We urge people to get organized and put an end to injustice.

Published on June 3, 2012 in Cherán, Michoacán

x carolina