Stillwater, Okla. —

A mild winter and spring that triggered early blooming and plant maturity, preceded by last summer’s record heat, is re-focusing attention on the controversial notion of whether the globe is on a warming trend.

The shifting patterns not only impact crops and livestock but also wildlife, an increasingly important component of many farms and ranches.

“With most biologists here, it’s a worrisome issue to them,” said Fred Guthery, a retiring wildlife ecologist at Oklahoma State University who hosted a recent quail symposium with wildlife managers from surrounding states. Climate change got top billing among an array of factors affecting the small ground-dwelling birds, which are the basis of lucrative hunting leases in Texas and neighboring states.

When asked how concerned his colleagues in other areas of the agriculture department such as agronomy and animal science are about climate change, he said, “It’s not an issue to them at all.”

Steven Smith, a wildlife and fisheries consultant with the Noble Foundation in Ardmore, Okla., who was in the audience, had a slightly different interpretation. He described attitudes toward global warming as “split down the middle” within the wildlife community.

He thinks of it as largely a generational issue.

“My dad and granddad aren’t buying into it, but I’m more open to it,” he said.

Wildlife managers might be more concerned about climate change than ranchers because they have less ability to directly alleviate the impacts on wild species, he added.

“We can’t bring grasshoppers to our quail,” he said.

Weather more extreme

U.S. weather is definitely making headlines. The hottest 12-month period going back to 1895 was recorded from May 2011 to April 2012. This year has already produced the hottest March, the third warmest April and the fourth warmest January and February on record.

“We are well on our way to seeing the records for warmest January-May and March-May periods absolutely shattered,” reported Associate Oklahoma Climatologist Gary McManus recently.

Regionally, droughts seem to be coming in more frequent intervals and are more extreme.

One or two years of deviation from the norm do not constitute “global warming.”

Because changes in average temperatures happen so gradually, people tend to be skeptical whether it is happening at all, said Jeff Lusk, upland game program manager for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, who spoke at the symposium.

A perfect example was the winter of 2009-2010 that brought exceptionally cold temperatures and loads of snow to the region, temporarily dispelling the notion that the earth is warming.

A mild winter and spring that triggered early blooming and plant maturity, preceded by last summer’s record heat, is re-focusing attention on the controversial notion of whether the globe is on a warming trend.

The shifting patterns not only impact crops and livestock but also wildlife, an increasingly important component of many farms and ranches.

“With most biologists here, it’s a worrisome issue to them,” said Fred Guthery, a retiring wildlife ecologist at Oklahoma State University who hosted a recent quail symposium with wildlife managers from surrounding states. Climate change got top billing among an array of factors affecting the small ground-dwelling birds, which are the basis of lucrative hunting leases in Texas and neighboring states.

When asked how concerned his colleagues in other areas of the agriculture department such as agronomy and animal science are about climate change, he said, “It’s not an issue to them at all.”

Steven Smith, a wildlife and fisheries consultant with the Noble Foundation in Ardmore, Okla., who was in the audience, had a slightly different interpretation. He described attitudes toward global warming as “split down the middle” within the wildlife community.

He thinks of it as largely a generational issue.

“My dad and granddad aren’t buying into it, but I’m more open to it,” he said.

Wildlife managers might be more concerned about climate change than ranchers because they have less ability to directly alleviate the impacts on wild species, he added.

“We can’t bring grasshoppers to our quail,” he said.

Weather more extreme

U.S. weather is definitely making headlines. The hottest 12-month period going back to 1895 was recorded from May 2011 to April 2012. This year has already produced the hottest March, the third warmest April and the fourth warmest January and February on record.

“We are well on our way to seeing the records for warmest January-May and March-May periods absolutely shattered,” reported Associate Oklahoma Climatologist Gary McManus recently.

Regionally, droughts seem to be coming in more frequent intervals and are more extreme.

One or two years of deviation from the norm do not constitute “global warming.”

Because changes in average temperatures happen so gradually, people tend to be skeptical whether it is happening at all, said Jeff Lusk, upland game program manager for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, who spoke at the symposium.

A perfect example was the winter of 2009-2010 that brought exceptionally cold temperatures and loads of snow to the region, temporarily dispelling the notion that the earth is warming.

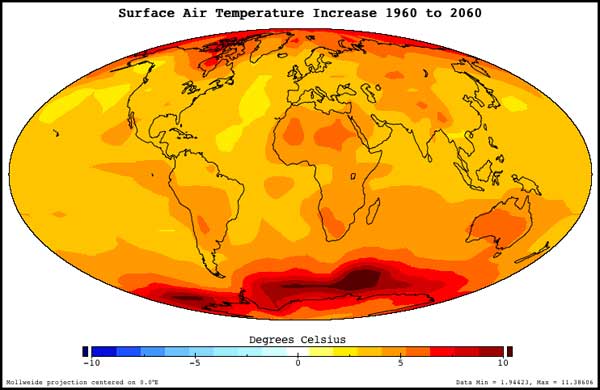

But Lusk showed a map revealing that colder-than-normal temperatures were concentrated only over the U.S. and Canada as well as Northern Asia that year while the rest of the globe remained warmer than normal.

Additional graphs indicated an increase in extreme weather events. “A lot more storms are qualifying as billion dollar storms,” he said. People who have been victims of one of those events are more likely to believe climate change is real, he added.

Experts admit there are many unknowns and that plants and species are affected by warming temperatures differently.

Some animals, such as coyotes and wolves, deer and caribou, and even armadillos, could actually benefit from warmer temps, according to researchers at the University of Washington.

In the case of quail, rising summer temperatures shorten the nesting season, limit re-nesting opportunities, reduce clutch sizes and compromise the synchronicity of hatching, all of which reduces hatching success and hurts the population of young birds, according to Kelly Reyna, the director of a large quail research and outreach program at the University of North Texas at Denton.

In addition, their ground-dwelling habits and small body size make them more vulnerable to heat than larger game birds that roost in bushes or trees. “Bobwhites need the shade,” he said.

Quail numbers have declined 80 percent since the 1960s, according to Reyna. Bag limits have been proposed in some parts of Texas but have not been popular. Firm public opposition will likely also keep the bird from being recommended for the endangered species list, he said.

Likewise, for political reasons, Guthery admitted that the topic of climate change is “a very tough issue to deal with.”

He liked a term Lusk used during his presentation. “No-regret management” refers to approaches aimed at mitigating some of the potential impacts in a way that would not be detrimental if predicted warming patterns don’t occur. One example was managing roadsides to create additional wildlife habitat.

While Lusk claims the vast majority of scientists believe global warming is occurring, Oklahomans in general are more skeptical. Republican Senator Jim Inhofe of Tulsa, the ranking member on the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, is considered one of the nation’s staunchest critics of global warming theory.

Jim and Sara Shelton, ranchers in attendance from Vinita, Okla., summarized the conflicted feelings they have about the topic.

The couple said the weather appears to be changing based on personal observation, and farmers and ranchers don’t have the luxury of putting their heads in the sand. “I think we’ve had enough extreme events the last 18 months that we know something’s going on,” Sue Shelton said. “If it effects the weather, we have to think about it.”

On the other hand, she also revealed why it’s controversial within the farm community.

“I don’t like it when they start talking about cattle causing methane gas,” she said. “Yes,” her husband added, “watch out for all of those belching cows.”