by Joaqlin Estus / Indian Country Today

Two Alaska Native corporations are working to develop what would be one of the world’s largest gold mines while some of their shareholders oppose it and more than a dozen area tribes have joined in a lawsuit against it.

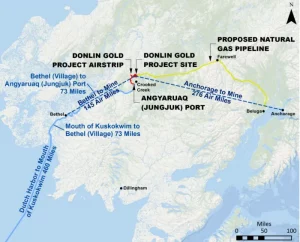

The Donlin Gold mine would be situated on a tributary of the Kuskokwim River, 275 miles west of Anchorage. Several Alaska tribes are concerned about harm to the river. The river provides habitat for salmon, a key subsistence food for more than a dozen Yup’ik villages downriver.

Three federally recognized tribes held a virtual press conference last week with the Center for Science in Public Participation, and Earthjustice Alaska. The tribes represent the communities of Bethel, Chevak, and Kasigluk.

Bethel is one of the communities downriver, 73 miles from the proposed mine. It has a two thirds Yup’ik population of 6,500 and serves as a regional hub for transportation, medical services, fuel, and groceries.

Participants urged mine opponents to ask the Biden administration and the state of Alaska to stop further permitting and development of the Donlin mine. In a statement, they said “Donlin does not have social license to move this project forward. It will destroy vital salmon spawning habitat and is an existential threat to our ways of life.”

Donlin Gold calls the estimated 33 million ounce reserves at the proposed mine site a “rare find.” If developed, the mine is expected to produce more than a million ounces of gold annually for 27 years.

Some 3.1 billion tons of waste rock would be excavated from an open pit mine 2.2 miles long, a mile wide, and up to 1,850 feet or 170 stories deep. The project also calls for construction of facilities such as a port, an airstrip, a 300-mile gas line, roads, and a water treatment plant.

Tribes vs Native corporations

The proposed mining site is owned by two Alaska Native for-profit corporations created under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971. The regional corporation Calista owns the subsurface rights. The Kuskokwim Corporation, which represents 10 villages in the Kuskokwim River area, owns the surface estate.

Beverly ‘Kikikaaq’ Hoffman, Yup’ik, is a tribal citizen of Bethel’s Orutsararmiut Native Council. She’s also a Calista shareholder. At the press conference, Hoffman said she’s one of many Alaska Native corporation shareholders who oppose the mine.

She said 300 shareholders in 2019 wrote to Calista. “Our letters stated we are Indigenous women of the Calista region with strong physical, emotional, and spiritual ties to the people and the land.”

Hoffman said due to potential mining impacts such as warmer river water temperatures, contamination, and destruction of habitat for salmon and other wildlife, “we are in fear of losing our way of life with what is proposed to be the largest open mine ever developed.”

The Final Environmental Impact Statement on the project describes potential impacts to subsistence including reduced harvest levels, restrictions on access, increased competition for resources, and sociocultural changes related to employment and shift work.

“The food nature provides is a lifeline,” Hoffman said. “Harvesting, preparing, sharing has always been a part of our Athabascan and Yup’ik way of life… It’s our responsibility to ensure that they are practiced decades from now. We want economic opportunity for all of our families, but not if those opportunities put our fish, moose, caribou, seal, walrus, berries, plants, and birds at risk,” she said.

Hoffman said shareholders have asked but Calista refuses to hold a shareholder vote on mine development. Instead, she said the decision to approve the mine “was made by a board of 11 directors swayed by misinformation” from Donlin, and “caught up in the corporate mentality of making the almighty dollar. And, in my humble opinion, they forgot the people they represent.”

Another Calista shareholder, Ananarour Sophie Swope, Yup’ik, said, “I know my offspring will have the same gut biome I do, which is one that finds our nutritious foods that are so perfectly provided as soul food. I don’t want to start a family if I don’t have access to our traditional foods.”

Subsistence is important to the economy of rural Alaska. Food shipped in from elsewhere is expensive, and Swope said, unhealthy. “I don’t want to turn to highly processed or microwavable foods that will give my children metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or even worse, cancer. This is my generation’s future.”

Lawsuit and SEC oversight

Olivia Glasscock is a senior associate attorney at the nonprofit environmental law firm Earthjustice Alaska, which is representing mine opponents.

“Most of the federal and state permits have been issued, but importantly we’ve identified substantial issues with some of these permits that really go to show that the permitting agencies are not working to protect waterways, human health, tribal sovereignty or ways of life in the region,” Glasscock said at the webinar.

“So we’re currently involved on behalf of Yukon-Kuskokwim tribes in two pieces of litigation in Alaska state court concerning the Clean Water Act Certification and the Pipeline Right of Way issued for the mine,” she said.

The tribes said the proposed mine would not meet water quality standards for protection of salmon habitat, for temperature and for mercury. An administrative judge earlier ruled the certification should be rescinded, however, the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation upheld the certification. Tribes are appealing the state’s decision.

Glasscock said the company needs both the water quality and right of way permits to proceed. “But importantly if either of those pieces of litigation are successful the permits would be rescinded and would go back to the agency. And basically they would have to start back at square one and Donlin wouldn’t be able to proceed unless, and until they were to get a new version of either of those permits.”

Novogold, one of the two parent companies of Donlin Gold, has completed an Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) statement, which provides information for investors who want to invest in companies that are environmentally sustainable. The information is reviewed by the Securities and Exchange Commission, which last year announced it would enforce regulations related to ESG and “identify any material gaps or misstatements in issuers’ disclosure of climate risks under existing rules.”

The two parent corporations of Donlin Gold, Barrick and Novogold, are updating a feasibility study of the mine.