A conversation with Panagioti Tsolkas, on Alligator Alcatraz and the fight against toxic prisons

Tule Lake internment camp, CA, 1943 / Alligator Alcatraz detention camp, FL, 2025

By now, you’ve probably heard of Trump’s latest white-terror marketing campaign: the ICE concentration camp hastily erected in Florida’s Everglades and officially dubbed Alligator Alcatraz. The $450-million ad-hoc prison opened last Tuesday, flooded on Wednesday, and began receiving detainees on Thursday. It consists of chain-link cages and FEMA trailers surrounded by more chain-link and razor wire, and is located about 45 miles west of downtown Miami, in the middle of a vast swamp. According to officials, the camp’s current capacity is 3,000 and will expand to 5,000 in the coming days.

Testimonies from detainees are already emerging, and the conditions they describe are as horrifying as they are predictable:

“They only brought a meal once a day and it had maggots. They never take off the lights for 24 hours… We’re like rats in an experiment… I don’t know their motive for doing this, if it’s a form of torture. A lot of us have our residency documents and we don’t understand why we’re here” -Leamsy La Figura, Cuban reggaeton artist and a detainee at Alligator Alcatraz.

A few hundred miles to the north, Florida is preparing to break ground on a second detention center at Camp Blanding, a National Guard base, with construction set to start this week. Meanwhile, Congress just passed a sweeping immigration and border enforcement budget with the aim of massively ramping up deportations, while Trump continues to send masked ICE gestapo and their military escorts into cities across the country (including 200 Marines just deployed to Florida) and Republican governors compete in the reality TV show known as the news for who gets to stage the next concentration camp Schadenfreude show.

To discuss the deeper context of this madness, the intersections of prisons, ecology, and human health, and lessons learned from past campaigns to stop, shut down, and improve conditions inside prisons and detention centers, I spoke with Panagioti Tsolkas, co-founder of Fight Toxic Prisons and Everglades Earth First!, a former editor at Prison Legal News and the Earth First! Journal, and a former staff organizer with the Florida Immigrant Coalition and the Center for Biological Diversity.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What do you know about the new ICE concentration camp in the Everglades and the area where it’s located?

In the late 1960s, officials in Dade County envisioned a massive airport in the Everglades, at the same site as the new detention camp. The original plan included six runways, covering 39 square miles. It would have been five times the size of JFK Airport, but in 1970, after only one runway was built, environmentalist and Indigenous opposition halted further construction. That fight led to the creation of Big Cypress National Preserve, adjacent to Everglades National Park, which was established as the country’s first national preserve in October 1974.

The Everglades was also the first national park in the U.S. created primarily to protect biodiversity. It was established in 1947 specifically to preserve the unique subtropical ecosystem, representing a shift from protecting places only for their scenic landscapes and tourism value. That said, it’s still epic as hell out there. If you can get a few feet off the ground, you can see for miles, like you’re standing on a mountain peak. It’s a vast wetland, with a mix of freshwater and saltwater, including sawgrass marshes, mangrove forests, and tropical hardwood hammocks. It’s also home to a vast diversity of species, including many that are endangered or threatened, including the last big cat roaming east of the Mississippi: the Florida panther.

Aside from that, the Everglades provides major water purification and flood control for the surrounding region, which supports millions of people. The area is also home to descendants of a resistance movement famous for kicking the U.S. government’s ass in the longest, costliest, and bloodiest of all the “Indian Wars” waged by the murderous psychos behind Manifest Destiny. That conflict is considered a precursor to the U.S. Civil War, because the Florida swamps also served as a refuge for Africans escaping slavery, who established Maroon communities there and integrated into some of the native tribes. The empire invested millions into the war because it knew that the alternative would be to watch a global slave revolt spread north from the Caribbean, as Haiti had demonstrated was possible only a few decades earlier.

Many Seminole and Miccosukee were forcibly displaced in the Trail of Tears and resettled in Oklahoma, but hundreds survived by staying in the swamps, where soldiers were scared to go. Some of the families never opted into the 1957 and 1962 formation of federally recognized Tribes, instead retaining their earlier claims to ancestral lands. This is why it’s such a huge deal to see native youth standing side by side with “immigrants” (people native to other parts of the continent and islands) and refugees descended from African slave revolts more than 200 years ago, holding signs saying “What Would Osceola Do?”1

Residents protest the Alligator Alcatraz concentration camp in the Everglades, near Ochopee, Florida. Photo: Giorgio Viera

Two weeks ago, the Center for Biological Diversity and Friends of the Everglades filed a lawsuit to stop construction of the facility. What is the status of that lawsuit?

The lawsuit asks for an injunction until there are environmental reviews of the project’s impacts, per the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requirements. This concentration camp—or internment prison, however you want to view it—was thrown together in a matter of weeks, using the same sort of exceptions that allowed for the construction of walls through sensitive desert habitats and traditional Indigenous lands along the southern border. It’s reminiscent of what Arizona’s governor did with the rogue junk wall of shipping containers a few years ago (which the Center for Biological Diversity also sued over). In that case, a combination of direct action and legal challenges forced the federal government to uphold its own laws and take the wall down. This time, the feds are cheering it on. And they’re promising to pop up more of these prison camps all over the country. The court should rule on the injunction as early as this week.

How else are people resisting efforts to turn the Everglades into a militarized site of mass detention and deportation? What communities are on the frontlines of this struggle?

We’re seeing organized communities from surrounding areas showing up in large numbers, especially youth. This includes people from Immokalee—home to the famous Coalition of Immokalee Workers alliance—as well as folks from rural towns like Palmdale, where residents, with the support of groups like Earthjustice, Sierra Club, Earth First!, and other organizations, have a legacy of fighting and winning land-use battles in recent decades, like the fight to access and protect Fisheating Creek.

Urban immigrant youth from Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Lake Worth, Fort Myers, and Naples are also coming out, along with hydrologists, biologists, and other scientists who have worked on protecting the watershed and its biodiversity. Notorious nature photographer (and neighbor to the site) Clyde Butcher has been out there, and the hook-and-bullet crowd of conservation sportsmen who want access to Big Cypress are raising hell too. They don’t want stadium lighting and traffic fucking up their hunting and fishing spots. Obviously there are some differences in priorities, but people on the ground are hashing them out together, working through them. There is incredible potential in that.

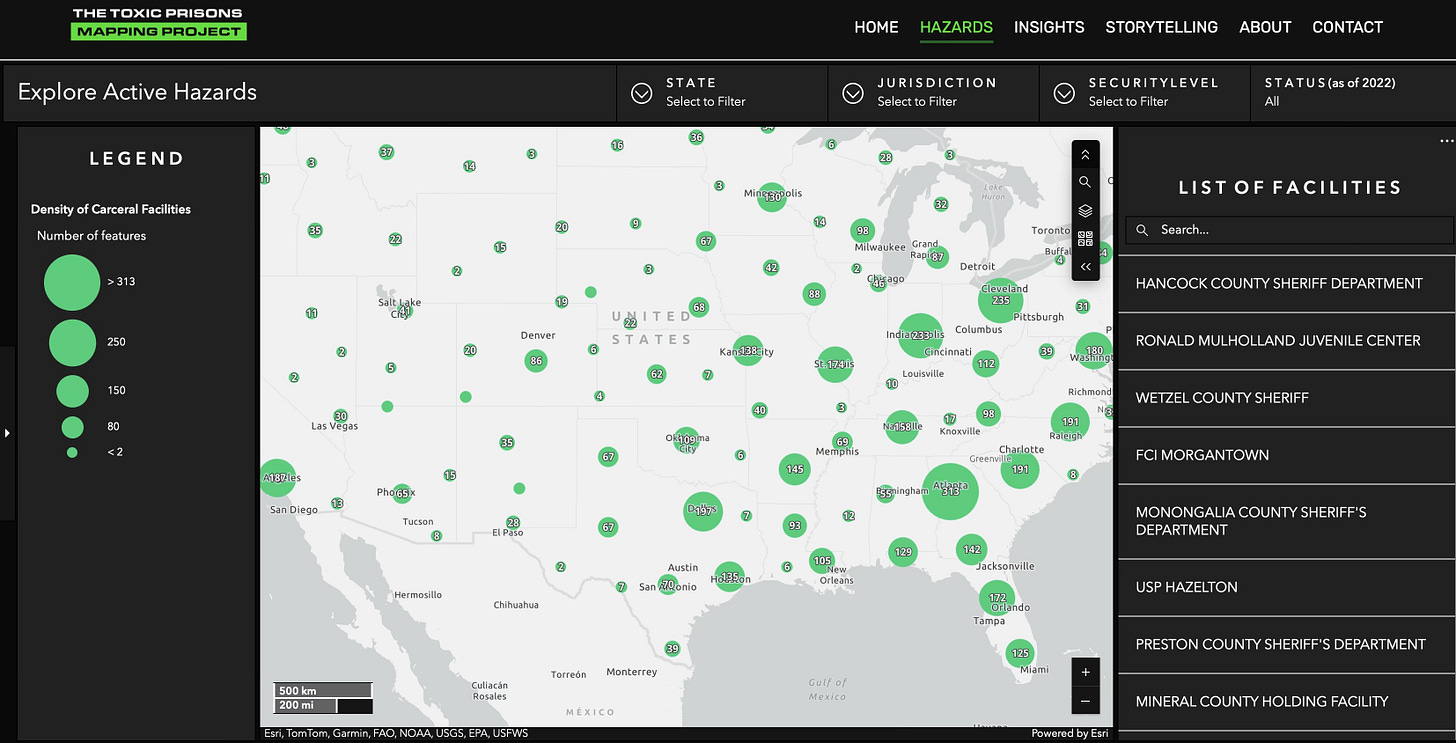

What is the campaign to Fight Toxic Prisons (FTP)? How are prisons connected to issues of ecology and human health?

I’ve been researching, writing and organizing at that intersection a lot over the past ten years. Thanks to the work of activists, academics, prisoners and their families, we have a significant body of work drawing these connections.

Prisons have the 24/7 pollution output of a small town, packed into a factory complex. On top of that, the populations inside are vulnerable to some of the worst impacts of climate and environmental injustice. People are literally trapped in cages while toxic floodwaters rise. Just to the north, in Manatee County, a few years ago prisoners were stuck in the flood zone of a phosphate mine-waste disaster. In Florida, prison labor is used to clean up after red tides and the toxic aftermaths of hurricanes.

In prisons across the country, prisoners experience mental and physical health impacts from indoor environmental conditions unique to incarceration, including mold outbreaks, arsenic and radon exposure, Legionnaires disease, Valley Fever, sewage leaks… In a case I studied, a prisoner in Michigan documented a rare blood poisoning condition connected to prolonged exposure to methane from a sewage leak near his cell. A lot of us, I think, have either lived in houses or know people who lived in houses with indoor pollution, like black mold. But people don’t generally think about what it would be like to be stuck in a room full of black mold, with nowhere to go.

Everything in prison is just incredibly intensified. Take extreme heat. Some people might think that not having air conditioning is, like, a first world problem. But try going without air conditioning when you can’t get out of the building. In states like Florida and Texas, where prisons don’t have air conditioning, people are getting sick or dying from the heat.

The day after Trump opened the Everglades detention camp, it flooded. I mean, of course it did: it’s in the middle of a swamp. This all seems so obviously intentional. It makes me wonder to what extent these dangerous and toxic prison conditions are a deliberate part of the punishment. Or at best, a kind of organized abandonment.

Yeah, that’s the legacy of the prison system. If you can make people terrified by the concept of prison, then social control is more effective. So yeah, I think it’s a reflection of the broader strategy.

In terms of ICE detention, obviously the Trump regime can’t deport all the immigrants in this country. It’s impossible, and it would have adverse impacts on the richest of the rich, who depend on immigrant labor. We know the goal isn’t to remove every undocumented person; it’s to create a climate of fear and terror, to make people more controllable, more scared to speak up or act in their own interests. So making a big show out of “Alligator Alcatraz” is part of that plan—to say, “Look at this place you could end up.” They’re bragging about the conditions, about the lethal dangers. That’s the story they want in the news. And unfortunately, I think it’s really hard for us not to play into that fearmongering—they create a kind of win-win situation by highlighting how fucked up the conditions are, and then we amplify it because, well, it is fucked up. So the sum of the discourse sends waves of fear through people, making them want to hide, or avoid joining a movement, avoid joining protests, avoid organizing in their community in any way that’s visible.

What are some concrete ways people have organized against prisons in recent years, and can you articulate any strategies that movements have developed to break out of that feedback loop, where advocates and abolitionists end up playing into these narratives of intimidation and fear?

I learned a lot about prison organizing during the years that I was involved in developing the network that came out of the Prison Ecology Project and the Fight Toxic Prisons research collaborations. At that time, we were in touch with many family members of people in prison who had visitation rights and would share information with us, and with jailhouse lawyers on the inside, who were often more comfortable advocating for themselves or on behalf of others because they do it on a professional or semi-professional level, on the inside. I learned a lot from my experience organizing with those inside/outside alliances that I think could be applicable, especially around how to make organizing demands while moderating how much retaliation comes down on people, who may or may not even be involved.

That was something we saw a lot of during the prison strike organizing. Initially, we started by surveying people about their experiences with conditions in custody. And then the strike for the anniversary of the Attica prison uprising was announced and we shifted to communicating with people about the demands being made around that. From there, over the course of two years or so, we were able to build a lot of relationships and connections with people who were hungry to hear from the outside and wanted to participate. We were able to get mail in, we were able to set up phone calls with people, or figure out who had phones and who could access the email, and figure out how to communicate safely. At the time, it wasn’t as common to have tablets; now a lot of prisoners do. So we had a lot of those contacts, but then those connections started getting severed: visitations started getting cut off, access to mail has been drastically limited, in part, I think, in response to that organizing.

We did see people lose their visitation status, which was really hard for some of the folks involved in the organizing. We also saw a lot of people sent to solitary just for being suspected of communicating with outside organizers. But we learned that people wanted to take action, and they wanted to take risks, when they knew they had outside support. I think this has also been the case in detention center organizing. The Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma has a lot of examples of repeat hunger strikes, with some success having their demands met. There have also been major lawsuit victories, although those strategies didn’t work in other circuit courts like they did in the Pacific Northwest. But the general strategy and concept is still useful, of coordinating together and having prisoners lead the way on litigation efforts, as we did in our campaign against the Letcher County prison in Kentucky, by using the environmental review process to engage people directly in prison.

So those are some of the lessons off the top of my head, which might be relevant for what comes next. But realistically, I think we’re going to see a couple years where internment or concentration camps in this country are filled up by the thousands, tens of thousands, maybe a hundred thousand people. How we communicate with and keep track of those people is crucial.

We should also look to the experience of organizing efforts in ICE detention under Obama. There’s a documentary I recommend everyone check out, called The Infiltrators. It’s about an organizing effort that people may not have heard of, or maybe haven’t thought of in a while, about young undocumented activists who intentionally got themselves arrested with the goal of organizing inside detention centers—in this case, the Broward Detention Center in Florida. At the time, they knew that their low-priority cases gave them a really good shot of getting out relatively quickly, so the idea was to get inside and organize people, take down names and names of family members, and create support campaigns for as many folks as possible. This elevated the level of pressure, by identifying people and their stories and then figuring out technical entry points to campaign for those people to get out, based on medical conditions or other factors.

So looking back at that case, and others like it, where people used those kinds of tactics for inside/outside organizing, would be a good thing to do in this moment, while we’re watching all this infrastructure be built. We know it’s going to be different, in that there’ll likely be a lot of turnover—people won’t stay in these facilities very long—but that could also shift: we might actually see a situation where they’re able to fill the camps, but can’t get the deportation process running as efficiently as they’re talking about. So people might end up sitting in these facilities for longer than we think, and we should be prepared for that.

Prisoners raise fists during the Attica uprising, September 10, 1971. Photo: AP

Listening to Republicans promoting the Everglades concentration camp—laughing as they talk about detainees being eaten by alligators or dying in the swamp when they attempt to escape—I was reminded of the southern border, where the U.S. government uses wilderness to inflicting suffering and death under the pretext of containing the movement of people. Do you think, in the case of the Everglades, that all this posturing about alligators and snakes is pure political theater? Or could we really see a situation where security at the camp is relatively lax, with authorities relying on the wilderness to contain people, and detainees are escaping into the swamps?

I mean, there is a legacy of that, as I mentioned, with Maroon communities, self-liberated slaves, and Indigenous communities from farther north escaping into the Everglades to survive. I can’t really picture ICE agents chasing anyone into the swamps. The experience I’ve had with Earth First! actions where we were like, “Alright, now we’re going into this swamp,” the cops basically stopped at the water and just watched and waited. But no, I don’t think people are going to be eaten by alligators. I think that’s political theater. But I do think it’s possible that the legacy of people escaping into the swamp could continue. I mean, honestly, the facility doesn’t look that well built. They put it up in weeks. It’s just chain link fences. It reminds me of the junk border wall, or really any section of the border wall, where people regularly climb or cut through it with little to no difficulty. It’s political theater. But yes, people could end up lost out there, and it’s also maybe a scenario where communities could support people in surviving escapes.

That’s all hypothetical, though, of course. But it makes sense to be asking hypothetical questions right now, even if they seem absurd, and to look at other countries with other experiences of migrant solidarity organizing. This administration is obviously spreading itself very thin. It’s well resourced—I mean, Congress just forked over $170 billion or more for immigration control—but it’s also spreading itself thin in a way that looks a lot like other late-game empires grasping desperately to hold onto the meaningless aspects of their culture, like whiteness, or “American” identity. It’s possible that if they continue to build more of these chain-link facilities as symbolic gestures, to induce fear, but they don’t actually secure them that well, that we’ll have a situation similar to the border wall, where what’s perceived as this high-intensity security infrastructure is really just a bunch of, you know, floodlights that don’t actually turn on and fences that you can just cut through with an angle grinder.

In 2023, you wrote an essay recounting your experience with the Stop Cop City forest defense movement in Atlanta. You explain how the State of Georgia lowered the threshold for charging people with domestic terrorism—from an act that kills at least ten people to basically any protest that involves property damage. This, you wrote, mirrors a national trend: . “In response to anti-pipeline, anti-police and anti-Trump protests, legislators in nearly 20 states proposed similar bills in 2017. Since then, 45 states have considered new anti-protest laws, with 39 state and federal laws passed that attempt to weaken First Amendment rights… [and] the most egregious of them, Florida Governor DeSantis’ anti-riot law, criminalizes anyone who participates in vaguely defined ‘violent public disturbance involving an assembly of three or more persons.” What has been the effect of this legislation in Florida, and is the general atmosphere of heightened repression having its desired effect and discouraging people from fighting back?

In Florida, they didn’t end up using those anti-protest laws in court. I think a lot of it was also political theater. I got arrested right around that time, at a solidarity protest at a prison, and there was a lot of talk about how they were going to use the HB1 anti-protest bill that had just passed—but they didn’t. I can’t think of any cases where it affected people directly, in part, I think, because of all the pushback. The Cop City example is more relevant here, and we’re still seeing the effects of that right now. People charged in the RICO case are going to court any day now, so we’ll be learning more about how that plays out in the coming weeks.

In the case of opposition to the detention center, I think the atmosphere of escalating repression is having the opposite effect. Getting hundreds of people to show up out on Tamiami Trail in the middle of the summer is pretty rare. I can’t think of many other examples when that’s happened. Usually, for other protests, we’ll see a couple dozen people. So I would say it’s turning people out more than it’s turning them away.

How can people get involved in supporting folks in prison and detention? What are some actions people can take, either individually, or as an organized group?

I’m part of a working group of environmental and immigrant rights activists that’s pursuing legal challenges against proposed detention centers or expansions of existing facilities, and we’ve been having some interesting conversations. The lawsuit filed against the Everglades detention center is a template that we think could be applied to other proposed camps. So I think people can plug into ongoing organizing and support the groups that are filing these lawsuits. A lot of the time, it’s grassroots groups with people on the ground who have standing, and they don’t have a ton of money. In the case of the Everglades, there are bigger NGOs that work in that region and have a legacy of environmental lawsuits, but in places like Folkston, Georgia, just north of the Florida line, where there’s a proposed expansion, not as much. So we need to support those efforts and the people working on the ground.

I think there are about a dozen or so detention centers that are good candidates for environmental lawsuits. One of these facilities is in Leavenworth, Kansas. It’s a federal prison located on a military base that they want to expand into an ICE detention camp. As far as I know, no one is litigating that. So finding those local fights and providing outside support is a good place to direct energy.

The other thing that came out of the fight against ICE in the Everglades is a model that many of us in the Earth First! movement are familiar with: tracking down the contractors and putting pressure on them. Often, these companies are small outfits that don’t want bad publicity; other times, they’re huge outfits and this one facility is not make-it-or-break-it for them, so they’d rather just cut their losses and not be affiliated with it. Mapping out those companies and putting pressure on them accordingly is a good approach.

Just the other day, I saw that some of the contractors for the Everglades camp have been taping over the company logos on their trucks…

Yeah, people were like, “Hey, I just saw a mosquito control truck come out to the facility. I don’t know if they have a contract, but here’s their phone number, let’s call and ask.” I think doing things like that can be incredibly effective. You don’t have to know for sure: It’s a fine approach to say, “Hey, we heard you were out there. Do you have this contract? Do you know the harm that this is causing?”

That’s something anyone can do. And it’s something that’s happening. It’s hard to measure the success in the immediate term, but we saw how it can play out just recently, with Cop City, where some companies were basically like, “We backed out of this project because people smashed our windows.”2 So occasionally you get this little glimpse of how protests, or bad publicity, or relatively minor acts of damaging property or exposing someone in the newspaper might get them to change their mind about affiliating with a project.

It’s the old SHAC model, essentially. But that was so long ago, maybe we should call it the Stop Cop City model instead.

Osceola was a leader of the Seminole resistance against the U.S. government’s campaign of ethnic cleansing in Florida.

Reeves Young Construction, Quality Glass Company, and Atlas Technical Consultants all backed out of Cop City contracts in response to pressure campaigns.