by Dingane Xaba / Unicorn Riot

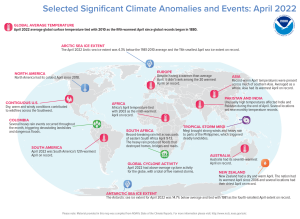

As the global climate change steadily increases, so too have its negative effects on the overall health of the world’s living species and their environments. Global temperatures measured in the first-half of 2022 alone have only confirmed this pattern as this year is yet again projected to be one of the hottest recorded years on record. As predicted, the increase in global temperatures has led to higher sea levels and drier weather conditions overall, which further increases the frequency and intensity of global natural disasters.

These disasters in turn, exacerbate the shortage of critically needed supplies such as food, water and fuel, while also exerting immense pressure on already fragile public infrastructure and ecosystems. While these disasters have been felt all around the world in the form of tropical storms, hurricanes and wildfires, none will feel these impacts more than the 40% of the world’s total population who live within 100 kilometers of a coastline.

In particular, the continents of Africa and Asia have been, and are projected to still be, the two continents most severely impacted by the negative impacts of climate change. In April 2022 alone, some of the highest global temperatures ever were recorded along with some of the worst natural disasters.

Of all these areas, no place has sustained more infrastructural damage and loss of life from natural disasters this year than the South African province of Kwazulu-Natal (KZN).

The KZN flooding of April 2022 is the worst natural disaster the country has experienced since the Natal Floods of 1987. The floods officially began on April 9, 2022 as heavy rainfall engulfed the land and would continue pouring for nearly five days straight.

At the time, KZN’s public infrastructure was still recovering from massive damage sustained during last year’s political unrest and was thus in an especially vulnerable position.

Low lying areas near sea level were quickly overwhelmed by the floods, prompting the municipality to issue a public advisory telling people to move to higher ground, if able. Mudslides triggered by the floods destroyed thousands of homes and informal settlements, especially those built on steep hillsides and shaky foundations. Visibility was severely reduced and entire highways turned into mighty rivers.

When the downpour finally lifted, large-scale damage to electrical infrastructure and roads made it very difficult to assess the full extent of the destruction. As a result, local authorities and media initially only reported a few dozen killed and missing, but as days went on, an increasing number of bodies were discovered underneath the piles of rubble. This prompted the government to yet again declare a state of disaster for KZN, and deploy some 10,000 South African National Defense Force (SANDF) troops to assist with recovery efforts. (Huge amounts of plastic waste debris also worsened the flood and led to ocean pollution, researchers have mapped.)

To date the floods are estimated to have killed 461 people with at least 23 people still missing and costing billions in infrastructural damage. All of this amounts to the 2022 KZN floods being the second worst recorded natural disaster in South African history.

Though many areas of KZN remain without electricity, residents fortunate enough to still have access to electricity in Durban were granted some relief when it was announced that the city would be exempt from all national load shedding (scheduled power cuts).

Load shedding refers to planned power outages that have been been implemented by the state-owned energy monopoly ESKOM, due to the worsening South African Energy Crisis. Surrounding areas, outside of Durban, however, were not granted this exemption, making Durban the only city in KZN and wider South Africa not currently subjected to load shedding.

Maxwell Mthembu, the head of electricity at eThekwini (Durban), would go on to clarify that it technically isn’t an exemption “since we lost between 700MW to 800MW, we have been trying to recover from it,” or in other words you can’t cut what you don’t have to begin with. Municipal authorities explained that this loss in power generation is around the same amount of electricity that is usually shed during the load shedding process and is therefore automatically considered load-shedding for the municipality.

Other hard hit areas in KZN outside of Durban have not been so fortunate. Since rural areas like Kwadukuza have reportedly experienced less damage to their infrastructure they have been denied the special exemption on the grounds that they haven’t lost the same amount of electricity as Durban. This justification of course doesn’t take into account the fact that rural area infrastructure is generally even less available, much less developed than the urban areas, and therefore could be the reason why surrounding rural areas appear to be less affected in comparison.

ESKOM has generally stuck to its promise not to implement any power cuts in Durban. However, power cuts did briefly return to the city in late June when ESKOM workers downed tools and went on strike demanding better wage compensation. ESKOM immediately blasted its workers who they say engaged in “illegal strike action” (otherwise known as a “wildcat strike”) and blamed the strike as the reason for raising the national load shedding level from it’s previous stage 4 to stage 6.

This is only the second time that stage 6 has been implemented in the now 15-year history of the South African Energy Crisis, suggesting that the crisis may still have to get worse before it can get better.

ESKOM would eventually cave to workers demands, inking a deal with unions for a 7% percent wage increase on July 5, 2022. The public utility also vowed to retaliate against union organizers by taking “disciplinary action against employees who engaged in a violent unprotected strike.” eThekwini municipality has since announced that regular load shedding will be returning to the city at the end of July. Despite drastic cuts in energy usage as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, 2022 has already been projected to be the worst year for load shedding.

The continued and worsening electricity shortages have also had an effect on KZN’s water shortage, as electricity is required for the city’s overburdened water pumps to operate. To date, many areas of the province are still without water as large water tankers continue to be shipped in, while engineers continue the immense task of fixing KZN’s largely out of date and heavily damaged infrastructure.

From the flooding, damage to Durban’s water aqueducts was so substantial that for the first time, the city announced water rationing measures to allow workers to make repairs. As such, many but not all, areas of the city will have their water supply cut for as much as four hours a day, as explained in the city’s water rationing schedule.

Despite all the negative press, it’s worth mentioning that South Africa’s infrastructure has shown incredible resilience under extreme circumstances. Public efforts to expand access to water and electricity to all citizens, has also made notable progress in the post-Apartheid era. For example, in terms of electricity, ESKOM estimates that since 1994, 7.2 million South Africans have been connected to the electrical grid.

While water quality and sanitation remain a serious problem, the most recent statistics from 2018 show that 89% of South Africans had access to water, yet another tremendous improvement compared to figures in the Apartheid era.

In fact, it may come as a surprise to some that South Africa is one of the only countries in the world to have the right to water codified in its Constitution. Perhaps even more surprising is the fact that in 2014, KZN’s largest city, Durban was internationally recognized for “its transformational and inclusive approach to providing water and sanitation services.” In a post that has since disappeared from its website, the Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI) heaped praise on Durban for being “one of the most progressive utilities in the world.”

Indeed South Africa has a long and storied history as a global leader in developing innovative technology in the water sector. One promising new innovation that could drastically help improve access to water, is the “Vulamanz filter.” This system was developed by researchers at the Durban University of Technology (DUT) and essentially functions as a portable gravity filter which can be used to purify contaminated rainwater or water from other public sources such as rivers. The system is easy to use and does not require electricity to function, a key detail considering the country’s ongoing electricity problems.

As the climate crisis accelerates, areas like KZN are increasingly bearing the brunt of its massive environmental, economic and social consequences. Much of these consequences were brought about by the disproportionate use of carbon emissions (CO2) in faraway, wealthier industrialized countries. Regardless of how it happened, the crises remains a daily fact of life for all the world’s population and as dire as the current situation is, there are still many innovate solutions and actions people are taking to reduce the severity of the crises.

If innovative solutions to tackling the climate crisis are to be found, then it is plausible that the severely impacted, yet highly resilient coastal province of KZN is ground-zero for discovering said innovations. After all the famous line that, “pressure makes diamonds, or bursts pipes” could not ring truer in a land which literally contains some of the largest diamond reserves and broken pipes in the world.