Maya history–and the civilization’s “collapse”–continue to occupy the minds of archeologists. Some research points to a series of droughts as playing an important role in the Maya demise. Other researchers propose the ancient Maya were less resilient to fight for survival due to religious beliefs.

And now Dr. Gary Feinman, an archaeologist at Chicago’s Field Museum, has suggested a new explanation. When he came face-to-face with a detailed map of trade patterns from an episode of Maya history–it was his “aha” moment, he said.

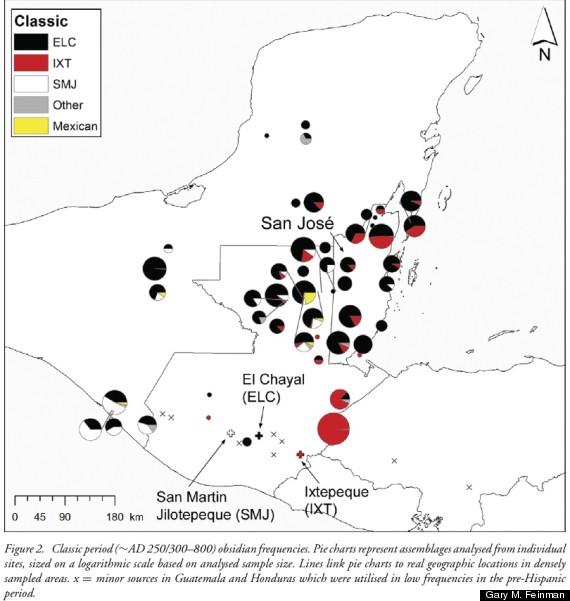

Dr. Feinman and a team of researchers from the University of Illinois at Chicago studied how the precious material obsidian, or volcanic glass, was traded and used by inland Maya communities during the Classic Period, just years before the mysterious Maya collapse.

When this research was displayed on the map, an interesting pattern emerged. The originally inland trade system evolved into a primarily coastal system, which suggested the inland Maya communities no longer had easy access to obsidian and other resources. After that, the populations in inland areas drastically declined.

“The collapse of these inland riverine centers has been a topic of discussion for a hundred years at least, and there are lots of ideas that have been put forth as possibly being responsible,” Dr. Feinman told The Huffington Post. “Our study suggests that at least one of those factors may have been this changing route of exchange and the decline of access–or ability of people at these inland centers–to get obsidian through the riverine trade routes.”

Eventually, the coastal trade routes grew in importance and the obsidian sources that were traded along the coast became predominant in the area. The researchers’ study doesn’t directly address why there was a shift in trade routes, but Dr. Feinman said there could have been conflict between communities, making the routes precarious or impassable.

“It’s really kind of astounding,” Dr. Feinman said. “Some of these data had been published before but when you look at the patterns of change graphically and you look at the maps… all of a sudden it’s sort of ‘wow.’ You see new things.”

Trade of any resource–not just obsidian–was important for Maya survival. But Dr. Feinman cautioned not to misconstrue this research as the ultimate explanation for the collapse of the Mayan civilization.

“People assume that when a civilization collapses it’s likely that there’s one catastrophic event that leads to that decline and generally that is not the case,” he said. “Even if a catastrophic event has an effect, it’s also because there’s some underlying issues, or tensions, or problems in the society before that environmental shift or change.”

While we’re going there, the whole idea of the Maya collapse is somewhat a misconception, Dr. Feinman said.

“Maya still exist today,” he said. “Mayan languages, aspects of their culture, still exist today. Certainly the DNA of ancient Maya still survive in living populations… So one misconception is the idea that the Maya disappeared, when of course they did not.”

Dr. Feinman and his research team’s findings were published online May 23, 2012 in the journal Antiquity.

Reblogged this on NonviolentConflict.