Reining in the anti-environmental far right

by Panagioti Tsolkas / Earth First! Journal

The Sagebrush Rebellion. That’s what ranchers, industrialists and right-wing libertarians of the U.S. West called their push, starting in the 1970s, to turn more public land over to grazing, logging and mining. Their main tool was a call for more “states’ rights” to control land-use decisions, but the underlying intention was privatization and profiteering. It was so “rebellious” that Ronald Reagan said in a 1980 presidential campaign speech, “I happen to be one who cheers and supports the Sagebrush Rebellion. Count me in as a rebel.”

So, more like the Sagebrush Status Quo.

Ten years ago, it seemed this so-called rebellion was hitting a stride, thanks to an armed standoff by the Bundys — a family of Mormon cattle ranchers and militia members in Nevada.

Eight years ago this month, the same family was in its second standoff, this time at the Malhuer National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon.

Today, the movement’s leader, primary spokesperson, and former candidate for Idaho governor, Ammon Bundy, is in hiding from the law, wanted on contempt of court charges stemming from a multi-million-dollar lawsuit against him after he recklessly called for an armed standoff at a hospital where a fellow militia member was beefing with staff.

While the Bundy’s militia movement seems to have crashed and be in the process of burning, what becomes of the sparks from this fire remains to be seen.

Let’s take a closer look at what these so-called Sagebrush rebels have been up to, whose been standing up them, and what it could mean for the future of public land and U.S. politics.

Lawless Cowboys in the Fight Against Public Land

Staffers from the Center for Biological Diversity — a spinoff of early Earth First!, where I now work — went to Malheur refuge in January 2016 to share a message in the face of the Bundy attack: That the land, protected by the federal government, is cherished by the public as a sanctuary for wildlife.

As architects of the armed standoff at Malheur, the family of militia cowboys illegally occupied the office at the entrance of the refuge to promote a bizarro and self-serving but incredibly dangerous worldview (more on that later). The presence of counter-protesters drove them into a frenzy. They accused Center staff of being federal agents, pawed at their pistols, and threatened that their snipers had counter-protesters in crosshairs.

In hindsight, that disastrous standoff bore seeds that grew into a much larger, deadlier conflict, one that the whole world watched live: the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Origins of the Bundy patriots

At the core of this story is the question of what “public land” means and whose interests it should serve. Movements like Earth First! and organizations like the Center believe it should do the greatest good, as determined by the best science available. At this point in the Anthropocene, the greatest good means urgently addressing the double crises of extinction and climate change that threaten all life on Earth.

But others take a different view on public land, longing for the good ol’ days of treating the Earth like a bottomless gold mine. Or in the Bundys’ case, an endless cattle ranch.

The Bundys say their family has ancestral and sovereign rights, since they claim to have worked their ranch since 1877. In reality, the land was previously promised to the Moapa band of Paiute Indians by federal treaty, but federal troops forced the Tribe out so the Bundys and others like them could settle in.

Back in the 1950s, the Bundy family started grazing cattle on land designated as the Gold Butte National Monument. It’s some of the driest and most fragile desert in North America. It also happens to be habitat for desert tortoises: imperiled reptiles protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1989.

In 1991, the federal government informed the Bundys that their grazing leases were canceled because they harmed protected tortoise habitat. In response, family patriarch Cliven Bundy made it clear that he had no intention of complying with federal laws aimed at protecting imperiled species or in any other way limiting his cattle operation. As a matter of fact, when the Bureau of Land Management staff approached him about canceling his grazing permit and paying for the damage his now-illegal cattle were causing, one of Cliven’s sons reportedly ripped up the documents in their face.

Standoffs against the public

In April 2014, the Bundy family invited a group of armed “patriots” — representatives of far-right-wing militias from across the United States — to their Bunkerville home and cattle ranch on adjacent federal public land in Nevada.

By this time, the Bundys were 20 years into ranching their livestock illegally on public land, using the conflict to peddle their anti-public Sagebrush Rebellion. Their core beliefs — that the federal government lacks authority to own public land, and that county sheriffs are the highest form of law enforcement — are rooted in hard-right racist ideologies created to sidestep federal civil rights laws by elevating local authority.

Sure enough, the Bunkerville gathering would turn into a standoff in which militia thugs with assault rifles stood down federal officials attempting to corral illegally grazing cows.

What consequences did the Obama administration bring against the Bundys for this lawless behavior? None.

Why not? It’s complicated. But among other things: White supremacy is a hell of a drug.

And so the standoff became a big win for militants. With no arrests or federal enforcement to deter it, over the next two years their movement grew, spawning more public land standoffs in the West, including one at an out-of-compliance small gold mining operation on BLM land in Josephine County, Oregon. And then in 2016 came the Malheur refuge office seizure.

The Bundys stormed the refuge in response to the arrests of the Hammond family: public land cattle ranchers who repeatedly violated terms of their grazing permit, harmed protected wetlands, set illegal fires, and made death threats against refuge staff. That itself was a disturbing shitshow, but the 40-day Malheur standoff, led by Cliven’s sons Ammon and Ryan Bundy, was worse.

This refuge, traditional land of the Burns Paiute Tribe, is considered a crown jewel of the national wildlife refuge system, protecting more than 187,000 acres of prime habitat in the high desert. It’s an important stop along the Pacific Flyway for hundreds of thousands of migratory birds: avocets, stilts, willets, killdeers, coots, phalaropes, rails, tule wrens, yellow-headed blackbirds, Caspian terns, pintail, mallard, cinnamon teal, canvasback, redhead and ruddy ducks, to name a few.

The seizure of Malheur showed clear signs of an escalating militia movement bent on attacking environmental policies. This time they took over a federal office building at an explicitly protected wildlife refuge, rather than just posting up at a failing land lease project. And, despite a hands-off approach by the feds, the confrontation ended in a death.

Thanks to the Center for Biological Diversity’s precarious presence at Malheur, we got to see the Bundy entourage up close. Their contradictory beliefs — often to the point of being nonsensical — were often animated by racism and a mindset similar to manifest destiny: The worldview that sparked a nationwide genocide of Indigenous peoples across the United States just a few generations ago.

Some of their actions could almost be commended for creativity. For example, they replaced the federal logos on refuge vehicles with the Harney County logo — because in their world, the county sheriff is the highest authority. It was a little reminiscent of the old Earth First! “No Deal Assholes” stickers on Forest Service trucks in the ’80s and ’90s, until you consider their ambition was to empower some of the most fascist tendencies across the rural U.S.

As the Center’s Kieran Suckling said about Bundy’s patriots, “This is a movement with violent, racist roots that aims to take us back a hundred years. It’s got no business in the 21st century.”

Members of the Burns Paiute Tribe witnessed white militia men desecrate their culture by bulldozing through sacred burial grounds in an attempt to build a road and handling ancient Paiute artifacts stored at the refuge office.

Before Malheur became a refuge in 1908, it was the Tribe’s traditional winter gathering area. Tribe members were moved to a 10-acre reservation near a landfill outside the small town of Burns. If anyone has a claim to the land, it’s them.

During the standoff, Burns Paiute Tribal Chair Charlotte Roderique suggested cutting the power to the refuge headquarters and waiting out the occupiers.

Jarvis Kennedy, a councilman with the Burns Paiute Tribe, found a silver lining in the paramilitary occupation. The standoff motivated tribal representatives and Indigenous activists from across state and federal borders to reach out, offering support. “As Native peoples, this Bundy stuff kind of kicked off something, like a unity thing,” he said, referring to the movement focusing attention on Native ancestral rights.

As if to prove his point, in the summer of 2016, Tribal nations across the continent joined together in an unprecedented show of solidarity at the Dakota Access Pipeline fight on Standing Rock Sioux land in North Dakota. That months-long protest camp brought together around 200 Tribes, many of which have not been united for over a century.

After Malheur

The encounter at Malheur entwined the Bundys and the Center for Biological Diversity. For starters, they still owe the Center money from losing lawsuits over the Bunkerville grazing violations. The org then got named in a bizarre civil suit by the family of a man who was killed by cops at Malheur, seeking more than $5 million for his wife and 12 children.

The Center continued speaking up, even after the sensational headlines faded and other environmental groups moved on. After tracking and documenting the standoffs, they continued confronting the Bundys in court.

They were on point, recognizing the threat for what it was. As the 2016 presidential election cycle progressed, it become clear that Malheur was bigger than petty vendettas and family feuds. The standoffs were essentially PR moves for what came next: rallying far-right militia support behind a viable presidential candidate.

Through a deeply fractured political realm, Trump emerged. And he came in swinging hard against environmentalists. He hardly sat down before reversing victories over the Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipelines. He promptly started plowing border walls through jaguar habitat. And then he pardoned the Hammonds, the father-son grazing team that inspired the Bundys’ actions at Malheur.

From the start of his campaign, Trump set off a steady stream of dog whistles calling to neo-Nazis, neo-Confederates, Three-Percenters, Oath Keepers, and Proud Boys: “patriots” one and all, rallying to do the bidding of drilling, mining, and cattle industries across the country.

Bunkerville goes to Congress

Jan. 6, 2021. We watched as a mob stormed Congress, flying Confederate flags alongside their Trump flags.

Sure enough, the failed coup attempt of Jan. 6 was headed up by some of the same militias who joined the Bundys at the Bunkerville ranch. Cliven didn’t attend, but he weighed in, and so did his son Ryan. They appreciated the spirit of the day but were disappointed by the execution. “It should have been something more,” said Cliven. “They should have held that capitol and corrected the problem.”

None of this is dead history. The impact of the Bundys’ militia rallies in 2014 and 2016 is still rippling through national politics.

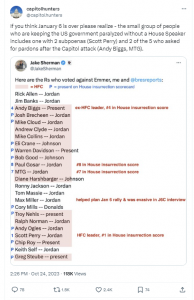

In fall 2023, we can pretty much draw a straight line from the Bundys’ ranch to January 6 — and then continue that line to the just-elected House speaker: U.S. Rep Mike Johnson (R-La), a pick from the far right and an election results-denier known as “Maga Mike” of the House Freedom Caucus.

While Ammon remains in hiding, Bundy cows are still grazing out at Gold Butte, standing as a testament to the Manifest Destiny of centuries past.

Another bitter taste of what could be in store for public land and endangered species if these mainstream militia supporters keep getting their way: Freedom Caucus representative Andy Ogles — who campaigned on pardoning the Jan. 6 coup participants — recently targeted the Center for Biological Diversity directly in his amendment to an appropriations bill.

Reclaiming righteous anger

Despite losing ground politically to these heirs of the Sagebrush Rebellion, in the past nine years environmentalists have won amazing victories for public lands all over the country.

The truth is, it’s okay to be pissed at the federal government, and a lot of local ones too. The Bundys and the right-wing militia don’t have a monopoly on anger.

Many of us wake up on most days livid at government agencies that aren’t doing enough to stop extinctions and thwart polluting industries. They’re spending way too much to build walls and weapons, with our money.

The most important takeaway from tracking the Bundys and the movement against public land protection is understanding that they’re not actually the rebels. They’re symbols of the status quo from the past 500 on this continent.

But we can choose to view them as the tail end of a dying worldview. Those of us who are fighting for public lands and the imperiled species they protect: We’re the ones fighting to change that established order, to put the Earth first.

Panagioti Tsolkas is a former editor at the Earth First! Journal and Prison Legal News. He currently works as digital communications staff at the Center for Biological Diversity. Cybele Knowles contributed to this story.

Please Protect our precious public lands

Cattle ranchers are the worst, and the Bundys are the worst of them. My best success as an Earth First! campaigner in the 1980s was getting the cattle out of a local state park. The ranchers opposing us were the worst people I ever dealt with as an Earth First! campaigner, even bringing guns to one of the hearings. The only use for these people is as compost, that’s all I can say about them.

Sorry, forgot to mention that the feds in the first Bundy standoff in Nevada weren’t exactly innocent either. Can you imagine what the feds’ reaction would have been if say, BLM demonstrators had pointed guns at them? But because it was ranchers, the feds backed down. They should have started shooting instead.

Public land, is what it says, Public Land for the public and wild animals. Lets keep it that wasy.